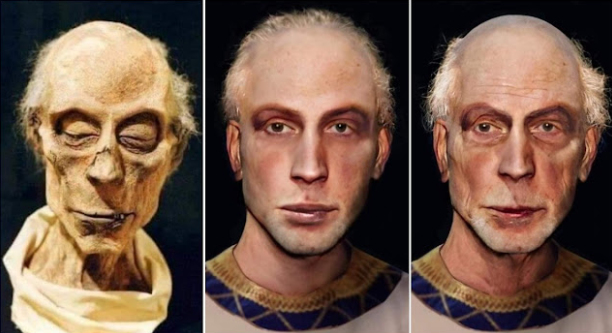

70 Million Mummified Animals in Egypt Reveal Dark Secret of Ancient Mummy Industry

In what is described as Egypt’s “dark secret,” a staggering 70 million mummified animals have been found in underground catacombs across Egypt, including cats, birds, rodents, and even crocodiles. But surprises awaited a research team when they scanned the animal-shaped mummies and found many of them empty!

A team of radiographers and Egyptologists from University of Manchester have used the latest medical imaging technology to scan hundreds of elaborately-prepared animal mummies which were collected from over thirty sites across Egypt during the 19 th and 20 th centuries, reports BBC News.

The biggest survey of its kind in history will feature in a BBC program by Horizon entitled “70 Million Animal Mummies: Egypt’s Dark Secret”, set to air this week (Monday 11 May). The documentary will examine the practices of animal mummification in ancient Egypt, and how so many creatures ended up bound and buried in catacombs.

The University of Manchester program used CT scans and X-rays to look into 800 mummies, dating between 1000 B.C. and 400 A.D.

Various animal mummies from ancient Egypt. Credit: University of Manchester.

The program will investigate the huge animal mummification industry of ancient Egypt, and why many of the carefully prepared, elaborately wrapped mummies were found to have no bodies inside.

In a press release by the University of Manchester, research leader Dr Lidija Mcknight said, “We always knew that not all animal mummies contained what we expected them to contain, but we found around a third don’t contain any animal material at all – so no skeletal remains.”

Many gods in animal form were worshipped by the ancient Egyptians. The mummified animals were considered sacred gifts and were used as offerings. Because this was such a popular religious practice, and demand was so high, some animals are thought to have suffered near or total extinction locally.

Animals and animal parts were preserved and wrapped to use as offerings in ancient Egypt. Wikimedia Commons

McKnight told The Washington Post, “You’d get one of these mummies and you’d ask it to take a message on your behalf to the gods and then wait for the gods to do something in return. That’s kind of their place in the religious belief system of ancient Egypt, and that’s why we think there were so many of them. It was almost sort of an industry that sprang up at the time and continued for more than a 1,000 years.”

Various animal mummies were examined during the study, including wading birds, cats, falcons and shrews, and a five foot long crocodile. Scans revealed that the mummified crocodile contained eight baby crocodiles which had been carefully prepared and bound together, and wrapped with the mother in one big crocodile-shaped mummy.

Mummified crocodile. Credit: University of Manchester

One cat-shaped mummy held only a few pieces of cat bone, and some artifacts contained no animal parts whatsoever, but instead held fillers like mud, sticks, reeds and egg shells, writes news site HNGN. The filler items were considered special as they had a connection to the animals and are thought to have served as symbolic remains.

Egyptian animal mummies in the British Museum. Wikimedia Commons

One of the catacombs contained around two million mummified ibis birds alone, and a network of tombs housed up to eight million mummified dogs.

These incredible numbers and the surprising way in which the bodies were preserved suggest that the animal mummification industry of ancient Egypt was huge.

The BBC reports, “some experts suggest animal mummies were being made to be sold to Egyptian pilgrims and so the ancient embalmers could make more profit by selling ‘fake’ mummies, others like Lidija believe its evidence the ancient embalmers considered even the smallest parts of the animals to be sacred [and] went to just as much efforts to mummify them correctly.”

The temple complex in Saqqara holds millions of animal mummies to this day, yet to be excavated and catalogued by experts. Molecular biologist Sally Wasef from Griffith University, Australia has collected samples of bones from these mummies in order to analyze their DNA and determine if they had been ‘farmed’ or intensely bred. It is thought that millions of animals were required for such a massive industry, described as a “national obsession.”

The artistically carved face of a mummified cat found in ancient catacomb in Egypt. Credit: University of Manchester

In 2011, Smithsonian curator Melinda Zeder spoke of the phenomenally large animal offering industry to the BBC, saying: “The ancient Egyptians weren’t obsessed with death – they were obsessed with life. And everything they did to prepare for mummification was really looking at life after death and a way of perpetuating oneself forever.”

“The priests would sacrifice the animal for you, mummify it and then place it in a catacomb in your name. So this was a way of obtaining good standing in the eyes of whatever god it was,” she noted.

Though the University of Manchester research raises many questions about the mummification industry, McKnight says the preserved offerings serve as tiny time capsules, allowing modern science a peek into the ancient techniques and rituals associated with religion, life and death.

The BBC program 70 Million Animal Mummies: Egypt’s Dark Secret, is set to air on BBC 2 on Monday 11 May at 2100.