Child Mummy Unlocks a Secret by Unravelling 450 Years of the Hepatitis B Virus

Scientists examining the mummy of a child who died in the 16th century have confirmed that the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has been causing human health issues for centuries. Strangely enough, it seems that the ancient strain of HBV found in the mummy hasn’t changed much over the last 450 years.

The team of scientists sequenced a complete genome of an ancient HBV strain by examining the mummified remains of a two-year-old boy who died around 1569, according to Science Alert.

The child was originally buried in the Basilica of Saint Domenico Maggiore in Naples, Italy. When the body was exhumed about three decades ago, sometime between 1983 and 1985, researchers saw pockmarks in various parts of the body and believed smallpox (the Variola virus) had caused the child’s untimely death.

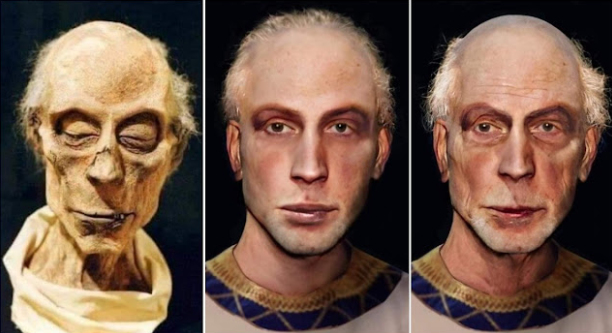

Pockmarks are visible on the face of the child mummy. (JD Howell)

Science Alert reports that the immunostaining and electron microscopy conducted at the time seemed to confirm smallpox. That case became known as the oldest evidence for smallpox in Medieval remains – and it has been used as a time stamp for researchers interested in the origin of that illness.

Ideas will have to change because the DNA testing and scanning electron microscopy on samples of skin and bone from the child mummy showed no signs of the Variola virus. However, the researchers didn’t find any evidence of Hepatitis B through the use of scanning electron microscopy either; instead they found particles of an unknown virus, which led them to suggest mummification may have an effect on viral particle appearance.

The mummy wearing funerary dress in the coffin. (Patterson Ross, et al.)

Apart from the necessary change in the time stamp for smallpox, this study also demonstrates how difficult it can be to identify which infectious diseases plagued a past body. Researcher Hendrik Poinar, an evolutionary geneticist with the McMaster Ancient DNA Centre and a principal investigator with the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, said, “These data emphasize the importance of molecular approaches to help identify the presence of key pathogens in the past, enabling us to better constrain the time they may have infected humans.”

The study may also help in modern times, when estimates suggest over 350 million people suffer from chronic Hepatitis B infections and about one-third of the total global population has been infected with HBV. As Poinar explained, “The more we understand about the behaviour of past pandemics and outbreaks, the greater our understanding of how modern pathogens might work and spread, and this information will ultimately help in their control.”

Hendrik Poinar, one of the researchers who identified the ancient Hepatitis B virus in the child mummy remains. (JD Howell)

The results of the study have been published online in the journal PLOS Pathogens.