Mummies of Six Sacrificed Children Found at 1,000-Year-Old Peru Site

Archaeologists from Peru recently discovered the remains of six mummified sacrificed children, who were apparently the victims of human sacrifice sometime between the years 1,000 and 1,200 AD. The sacrificed children were entombed near the mummified remains of an important aristocrat or wealthy individual, and it appears the children were chosen to be his companions on his journey into the afterlife.

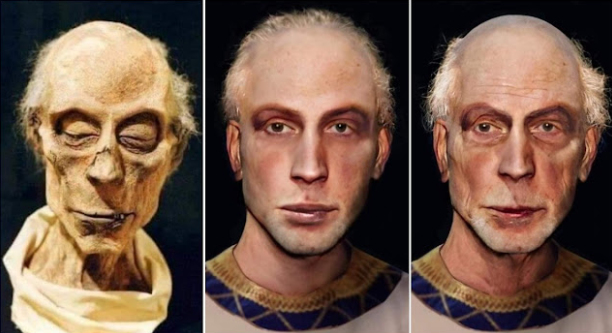

One of the six mummified sacrificed children, found at the ancient pre-Incan city of Cajamarquilla, Peru, which were apparently killed to be companions of an important person on his journey into the afterlife. These sacrificed child mummies were determined to be about 1,000 to 1,200 years old. (PHYS)

Peruvian Sacrificed Children: Companions in the Afterlife?

The mummy of the dead man, who was believed to have been approximately 20 years old at the time of his death, was originally discovered in November 2021 by archaeologists digging at the ancient pre-Incan city of Cajamarquilla. This long-abandoned adobe metropolis is located about 15 miles (24 kilometers) inland from Peru’s capital city of Lima, near the Peruvian Pacific coastline.

A closeup of the rope-bound adult mummy discovered with the six sacrificed child mummies, found at the Cajamarquilla archaeological site not far from Lima, Peru. (UNMSM)

Curiously, the mummified aristocrat was found bound with rope and with his hands posed to cover his face. The small skeletons of the children were tightly wrapped in cloth, mimicking the mummification of the aristocrat (but without the additional bindings). They were placed at different locations inside the tomb, but still close enough to the man to be clearly connected to him. The archaeologists believe the children did not die of natural causes but were killed intentionally so they could be buried alongside the important individual for whom the tomb was created.

“Andine societies believed that after passing away, people didn’t disappear,” National Major San Marcos University archaeologist (and Cajamarquilla excavation leader) Pieter Van Dalen told the international news agency AFP. “Death wasn’t an ending but a beginning, a transition to a parallel world.”

If a person was considered worthy enough by such a society, his people would want to make sure he didn’t have to make that transition alone.

“As part of the funerary rites other people [would be] sacrificed in his honor,” Van Dalen confirmed. “They were placed in the tomb’s entrance so that they could accompany him on the path of the dead.”

From the perspective of such cultures, death was not a tragic event to be mourned, but an adventure to be undertaken eagerly. In this context the people killed in human sacrifice rituals would not have been considered victims at all. Instead, they would have been seen as fortunate souls whose ascent to other realms had begun earlier than expected.

But why would children have been chosen to fill such a role?

Van Dalen speculates that they could have been close relatives of the nobleman. Since this individual was only about 20 years old at the time of death, they couldn’t have all been his children (although one or two could have been). That raises the possibility that they were siblings or cousins. Or perhaps they weren’t family members at all but were chosen as sacrificial victims for another reason entirely.

In addition to the children, somewhat farther away from the body of the aristocrat the archaeologists uncovered the remains of seven other adults, none of whom had been mummified. It isn’t known if they were also sacrificed to accompany the aristocrat into the afterlife, of if they died some other way and were simply buried in the same tomb.

Animal bones that belonged to llama-like animals were also unearthed in the burial chamber, along with the skeletal remains of a dog and those of an Andean guinea pig. There was also a significant supply of burial goods entombed inside the large grave, including ceramic pots, decorated calabashes (containers made from gourds), and knitting gear. Traces of corn and other vegetables were also found in the tomb, which combined with the animal remains suggest the man buried there may have somehow been connected with agricultural enterprises.

His young age raises the possibility that he was the son of a wealthy landowner, or of some other man who’d gained an enormous amount of power and privilege in his society.

The so-called ‘Dead City of Cajamarquilla’ was built sometime early in the first millennium AD by the Wari people. (Mi Peru / Public domain)

Exploring the Dead City of Cajamarquilla

The so-called ‘Dead City of Cajamarquilla’ was built sometime early in the first millennium AD by the Wari people. The sprawling inland desert site of the city covered over 413 acres (167 hectares) of land in total, and all of its buildings were constructed from adobe or mud brick. Excavations there have turned up well-preserved squares, cemeteries, canals, underground food storage facilities, and wide, multi-lane streets, plus enough housing to host a large population of permanent residents.

After the fall of the Wari Empire in approximately 1100 AD, the site was re-occupied by the Ichma people, who then established it as one of the centers of their small kingdom.

Given the preliminary dating of the mummified remains of the aristocrat and the children, it is likely they came from the Ichma culture. The Ichma were one of the most prominent of the pre-Incan people to live in the area around Cajamarquilla, and theirs was one of many small kingdoms that sprung up in the region following the implosion of the once-dominant Wari Empire.

First under the Wari and later under the Ichma, Cajamarquilla gained and retained great prominence as a commercial, administrative, religious, and military center. It was strategically located along travel routes that connected the interior Andes Mountain highlands with ancient Peru’s coastal areas, and that made it a prized possession for the peoples who lived there in pre-Incan era.

At the height of its prosperity, Cajamarquilla was a prosperous city populated by up to 15,000 people. Strategically located near the Rimac and Lurin River valleys, it was in a prime spot for irrigation, and the efforts of its people to supply water to the city while irrigating the surrounding land to encourage crop growth help the city thrive.

The Ichma culture reigned supreme in the region to the north and east of present-day Lima for more than 300 years, before the mighty Incas finally moved in and seized control of the territory at the end of the 15th century. By this time Cajamarquilla had actually fallen into disrepair, having been abandoned by the Ichma people as a result of climate-related water shortages and damage from earthquakes.

But while the city was left uninhabited for many centuries, its adobe foundations remained intact and well protected. Excavations that have taken place at Cajamarquilla over the past several years have been incredibly fruitful, and the discovery of the buried tomb and the 14 bodies it contained is just the latest exciting find this remarkable ancient site has produced.