Random Corpses are Becoming Mysteriously Mummified in Portugal

There is a shortage of cemetery space and graves in Portugal … but the cause has little to do with overpopulation and an increase in deaths amongst the living. No, Portugal has corpses stacking up in morgues because the ones that are already ᴅᴇᴀᴅ are turning into mummies and refusing to decompose. If this sounds like a new twist on the zombie apocalypse or on the Catholic and Orthodox belief that the bodies of some saints don’t decompose, the researchers are open for suggestions because they have no idea why the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ are mysteriously mummifying in Portugal. And brace yourself for the reason why this is causing serious problems for cemeteries, morgues and families of the deceased.

“This has a social impact, which is 𝚚uite a big deal for my own country.”

“This”, according to Angela Silva Bessa, a forensic anthropologist from the University of Coimbra who is doing research on Portuguese cemeteries, is actually a combination of things, starting with a lack of burial space across the country, which became so severe in the late 1950s and early 1960s that a practice was introduced in 1962 called “levantando os ossos” or “raising the bones.” Business Insider reports that like most other countries, the Portuguese had long buried their ᴅᴇᴀᴅ in small church graveyards and the parishioners had an understanding – when new bodies were added to a family plot, the old bones were removed and placed in a common ossuary or tomb.

In earlier times, decades could pᴀss before the need to exhume arose, but the shortage of spaces became so severe that in 1962 churches and cemeteries were allowed to treat burial plots as temporary, with a 3-to-5-year limit on occupancy before being removed automatically to the common ossuary – which could be a niche in the walls of the cemetery or cremated, a less common practice in Portugal. Morbid, yes, but society accepted it and the practice of “raising the bones” worked … until the demand for spaces became even greater. That led to another more morbid social impact.

The less time a corpse spends in a grave, the less time it has to decompose. Since families are notified so that they can be present when family members are exhumed and moved, they can view the decomposing remains of loved ones multiple times. Paulo Carreira, chief executive of the national funeral ᴀssociation of Portugal, says families seem to be OK the first time, but it is no surprise that the practice becomes emotionally draining. And now, something new is being seen that adds to the stress of the practice – bodies are being exhumed that haven’t decayed at all. It is these mummies which has brought Angela Silva Bessa in to determine what is happening.

Imagine going to the gravesite of a close relative for the burial of another relative and finding the first one completely preserved many years after their death. This is not 𝚚uite “incorruptibility” – that is the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox belief that the bodies of some saints and holy people do not decay because of a miracle of divine intervention. This doesn’t happen to all saints and is difficult to prove. A recent example was the body of Pope (and saint) John XXIII, whose body was said to be extremely well preserved when exhumed in 2001 – 38 years after his death – but many attributed it to the fact that it had been embalmed and kept in an airтιԍнт coffin.

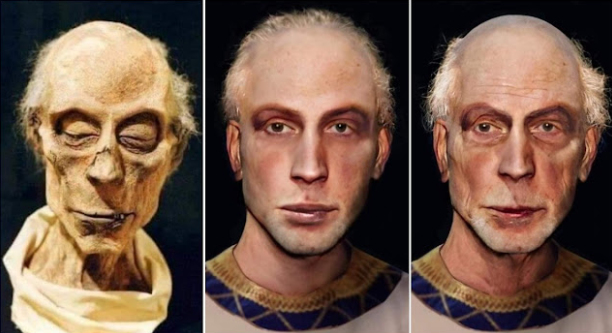

Bessa points out that this is obviously nothing like the intentional mummification practiced in ancient Egypt – a process that is only now becoming understood as more mummies are found and better tools for analyzing them without destruction are developed. However, this type of partial mummification is uncommon in Peru and other South America countries where the dry air in the mountains 𝚚uickly dehydrates and mummies corpses naturally and completely. Something strange is causing some bodies buried at the same time in the same cemeteries to mummify completely or partially, and at different rates in the same environment. Bessa entered her research with a hunch.

That is not a statement on the diet and obesity of the Portuguese by Krap, but it is close. He says one reason why some of these bodies are mummifying could be variations in size, muscle mᴀss and fat content. Another could the variations in the complex ecosystem that is in the soil in different locations in a cemetery (under trees; on a sunlit hill; in a poor drainage area) and between different cemeteries. Finally, Bessa says the lifestyle of the person, which may have hastened their death, could also have an effect on their after-death – decomposition and mummification may be related to what they ate, whether they smoked or took certain medicines.