Unearthed by nature’s force: A 16th-century mummy emerges in Ecuador following an earthquake, revealing a slice of history preserved across centuries. A seismic revelation of the past

A mummified Spanish monk found in the walls of an Ecuadorian church, alongside a mummified mouse.

IN 1949, AN EARTHQUAKE DEVASTATED the small town of Guano, Ecuador. As rescuers were searching through the rubble of the local church they made a bizarre discovery: a mummified body stashed in the walls, alongside a mummified mouse.

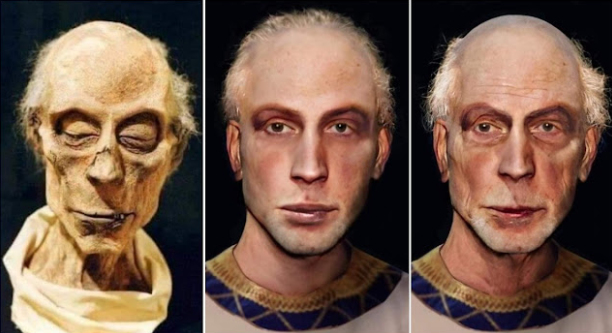

The Momia de Guano (Guano Mummy), as it became known, was discovered in its coffin inside the crumbling walls of the old La Asunción Church, built some 500 years ago. After a series of tests and plenty of research, investigators concluded that the mummified remains were those of Fray Lázaro de la Cruz de Santofimia, a Franciscan monk from Spain who had dutifully looked after the church in the mid- to late-1500s.

Upon his death at an estimated 55 to 60 years of age, he was buried within the church walls in what was likely a local tradition, allowing Fray Lázaro to care for his church even after his death.

The body appears not to have been mummified intentionally, or at least not by any standard mummification process. Instead, lime thrown onto the body at the time of its burial helped to preserve the corpse and along with it a little mouse who was found in an equally preserved state next to the monk. It’s unknown whether there was any kind of meaning behind the presence of the mouse (a loyal pet, perhaps?), or if it just had the misfortune to curl up in a lime-filled coffin.

Today the Guano Mummy lies in a hermetically sealed glass case inside the Museo Municipal de Guano. It’s a strange sight, partly because of its clothing, which makes it look more like someone’s mummified grandmother than a mummified Franciscan monk. Its head is covered with a purple headscarf; its body dressed in a long, white, jacket-like robe. According to museum guides, the headscarf was either put in place to keep the mouth from hanging open, or it was a local burial tradition.

Also inside the museum, at least when it’s not “on tour,” is a life-sized replica of the mummy, which cost the local municipality $2,200. It serves as a stand-in for the real and far more fragile mummy at various exhibitions and educational viewings that occasionally take place throughout the Chimborazo Province of Ecuador. The mouse, unfortunately, has no such replica.